In today’s article I wanted to introduce a concept used extensively by elite athletes and explain how this concept could be used in the fitness industry.

As a general comment, when looking for the latest trends in fitness, I believe we should always start with the elite market as this is where most of the cutting edge training methodologies are tried and tested. The great thing about this approach is that the elite market will typically have smoothed out the rough edges of any new concept and as adaptive fitness enthusiasts, we just need to have the know-how to take these concepts and modify them for our needs.

One concept that is gaining in popularity is that of the Acute:Chronic Workload Ratio (ACWR). This concept states that:

The ACWR takes into account the current training load (acute) and the training load that an athlete has been prepared for (chronic).

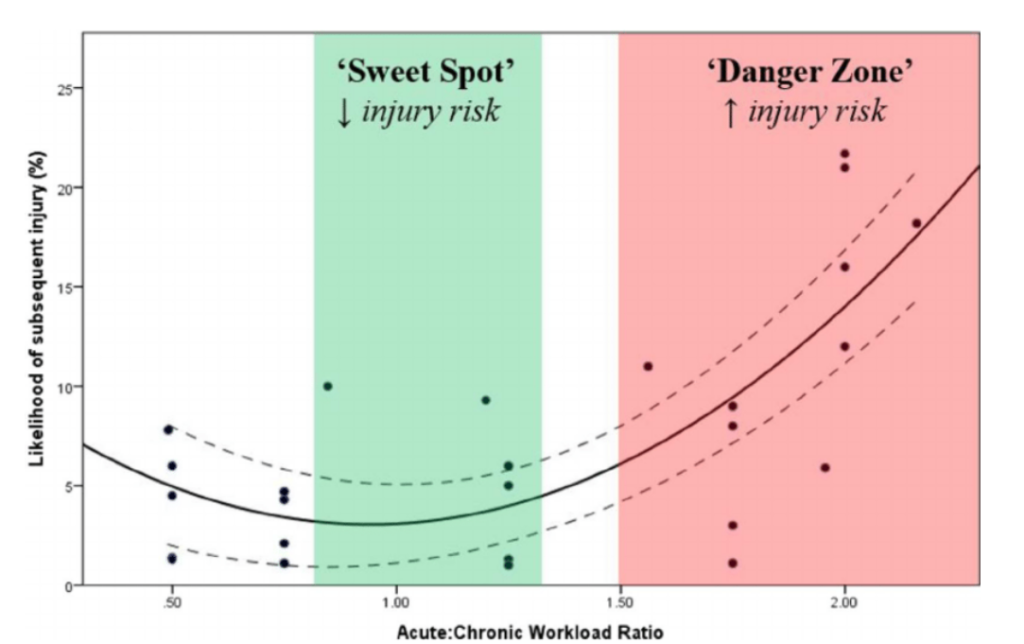

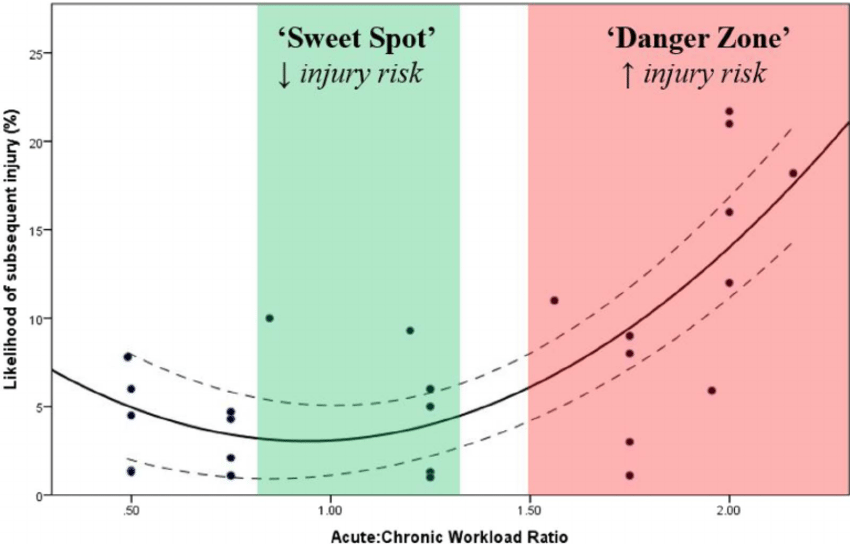

What this ratio indicates is the state of readiness of the athlete to train and the risk of injury due to an incorrect ratio of previous training loads to current training load. The typical “safe” ratio range is from 0.8-1.3.

Let me elaborate:

Let’s say that athlete A has been training 4 days per week over the past 4 weeks and we have been able to measure their total training load and we now have an average weekly training load for that past training period. This athlete now moves into week 5 and they have decided that they have some free time and so they dramatically increase their training volume and intensity. They now train 6 days in this week including a couple of double up days (for a total of 8 sessions during this week).

The ACWR states that if the athlete’s acute (current) training load is greater than their chronic (historical) training load by more than ~30%, the athlete will have put themselves at a greater risk of injury due to not having the training background to handle this rapid increase in load.

Let’s put some figures to this:

Previous 4-weeks of training (4-days per week) – Average weekly distance covered = 30km.

Current week of training (8-days per week) – Weekly distance covered = 50km

If we apply this ratio (Acute:Chronic) – we get a ratio of 50/30 = 1.67.

from the following graph, you see that any ACWR that is greater than 1.50 will increase the risk of sustaining an injury as the athlete doesn’t have the training background to handle this increased weekly training load.

What is equally important is that if you don’t train enough in any given week (compared to your previous weeks of training), you also start to increase the risk of injury as you are not doing enough work to maintain the physical fitness attributes you have developed and this puts you at further risk in the future if you then rapidly increase training load.

How does ACWR fit into the Fitness Industry?

If we look at the current market place, the current obsession with Crossfit would be a great candidate to incorporate ACWR into the training methodology being applied in gyms across the globe.

BUT, the entire premise of ACWR is to compare chronic training loads to acute training loads, so how can you apply this principle to your training if you aren’t accurately measuring your training load???

My biggest frustration coming from an elite athlete background now working in the fitness industry is the almost total lack of measurement of training load in most aspects of fitness training.

I don’t know of anyone in my gym that accurately records their weekly training volumes of weight lifted or reps & sets completed. So it is impossible to apply any scientific principles to your training routines if you are not capturing this sort of training information.

At least in the gym it is possible to record this information if you are willing to carry around your phone with an appropriate training App or even a paper based training diary.

If we look at circuits (eg Crossfit) – I have not met any Crossfitter who can tell me with any accuracy, what their total training load was for any given week. When asked “how are you monitoring your training load from week to week?” they often look at me blankly and shrug their shoulders.

Is it no wonder that there is such a high percentage of injuries with Crossfitters (particularly in the early stages of performing this type of fitness activity) – where their ACWR is almost always >1.50 week after week.

So let’s assume that you are keen to apply load management concepts to your training, what are you going to measure?

There are two ways of going about this – you can look to capture External load and/or Internal load data.

EXTERNAL LOAD

External load is the external stimulus applied to the you whilst training. It is the measurable physical work performed during training. Examples of external load metrics include:

GYM TRAINING METRICS

- Total weight lifted

- Total Reps/Sets

- Training Intensity (Weight lifted/unit of time).

OUTSIDE GYM METRICS

- Km covered.

- Number of sprints

- Player Body Load*

INTERNAL LOAD

Internal load is the physiological and/or psychological response to external loads. It includes measures such as heart rate, as well as subjective measurements such as ratings of perceived exertion (RPE). Examples of internal load metrics include:

- Heart rate*

- RPE (Rate of Perceived Exertion)

*A common way of measuring external & internal loads is by using wearable technology.

It is important to understand that identical external training-loads could elicit considerably different internal training-loads in two athletes. Meaning that the training stimulus (external load prescribed) may be appropriate for one athlete, but inappropriate for another (either too high or too low).

The above situation describes a typical circuit class, every participant (regardless of their training background) is required to complete largely the same amount of work (The weight might vary, but total load (repetitions/sets) are often the same!).

Thus, monitoring of training-load should be done on an individual basis when possible, and focus on the metrics that will provide the best insight for the individual.

So where to from here?

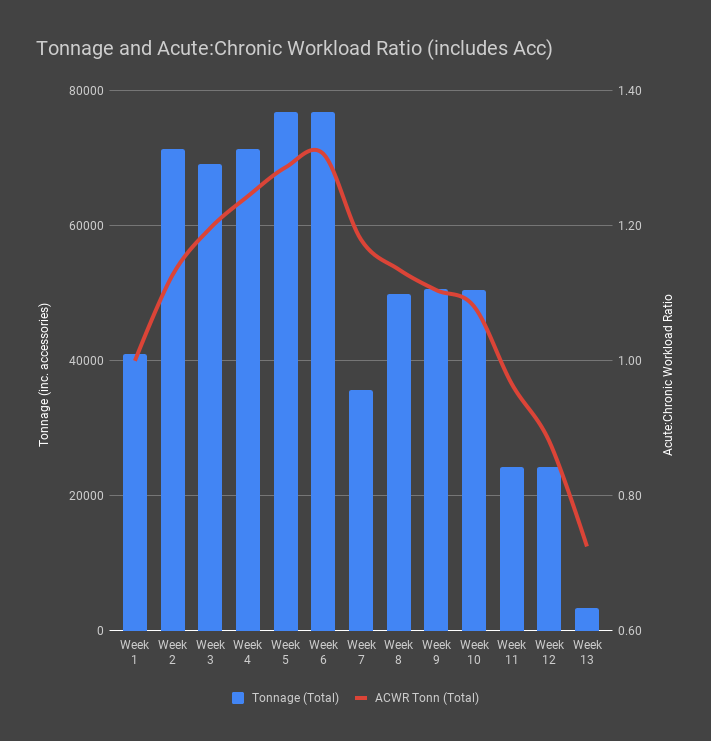

If you are interested in applying more advanced (sports science) principles to your training regime, as a starting point I would strongly suggest that you begin recording your total training loads (daily, weekly).

Initially, this could be nothing more than collating total sets, repetitions and load lifted in the gym and collate these at the end of each session. Plot these out on a graph over time and see how your training load varies from week to week (you might be amazed at the insight this information will give you which could show you why you are or are not getting the outcome you expect (eg if your training load is largely the same from week to week – with no progressive overload their can be no adaptation).

If you are completing regular circuit classes, I would suggest you record the following metrics:

1. Total exercise time (remove warmup, cool down, drink breaks).

2. Measure your heart rate throughout the session (using a chest or wrist based HR monitor). record the average and maximum.

3. RPE (how hard was this session today)? This is a subjective measure of how much the session physically knocked you around.

Once you have captured several weeks of training you can then begin to look at any patterns that may emerge.

Aside from the ACWR that you can apply to your historical training data, you can also look at two other very important training factors that we often ignore due to the lack of objective data to compare:

1. Progressive overload – you must over time increase at least one aspect of your training if you wish to continue to improve. This could be maximum weight lifted, total repetitions, sets, load, etc. Without this continued increased stress, your body will have no reason to change.

2. Periodization – your body better adapts to variation in training – you should look to have easy, medium and hard training phases (with an emphasis on easy/recovery phases regularly interspersed throughout your training year).

SUMMARY

1. Detailed recording of your total training loads can highlight key aspects of your training that can assist in maximising your gains and minimising potential injury.

2. Comparing current to historical training data (Acute:Chronic Workload Ratio) has been shown to be quite accurate in the detection of future training injuries.

3. Using a combination of both External & Internal load metrics can improve your overall understanding of how you are adapting to the training you are undertaking.

REFERENCE:

Tim Gabbett: To couple of not to couple? For acute:chronic workload ratios and injury risk, does it really matter?

Periodization II – Specificity, Adaptation and Reversibility.