Welcome back to the sprinting series – check out Part 1 of the series for my breakdown of my initial recommendations for programming for a sprint athlete. I’ll continue with more incorporations to your program below.

Vertical Load Generation & Tolerance

A key conditioning goal for all coaches of sprint athletes is to:

a. develop the appropriate strength/power to allow the athlete to generate the sorts of forces required at each ground contact, and

b. to develop the musculoskeletal system throughout the body to tolerate these loads with no collapse.

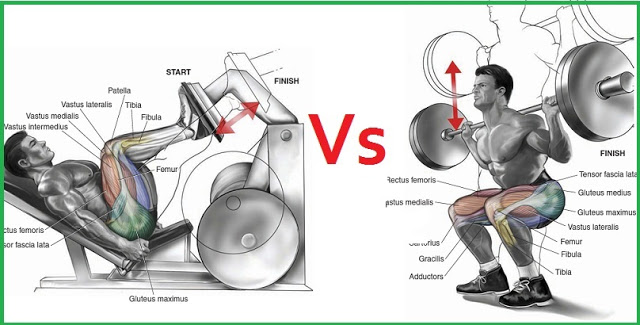

A mainstay of all strength and conditioning programs is that of the traditional squat (+/- 90o knee angle). As someone who has worked in the S&C space for >30 years I would like to put it out there that squatting is not a leg exercise, it is a core exercise!!

Why do I say that? As an experiment, have any of your athletes trial a 2RM squat maximum, then have them replicate the 2RM max test on an incline leg press machine – In 99% of cases the athlete will be able to leg press 2X+ what they can squat, so if squatting is a leg exercise why can’t they squat as much as they leg press? It is because the core is the limiting factor in squatting, not the legs. So if traditional squatting is your primary leg strengthening exercise for your athletes, then you are effectively developing ~50% of their leg strength potential doing this exercise only!!!

Of course I understand that the majority of coaches don’t just have their athletes squat, but I do see a high emphasis on the squat movement when there are many other movements that are much more effective to develop the required strengths for effective sprint performance.

Back to our force generation and load tolerance dilemma.

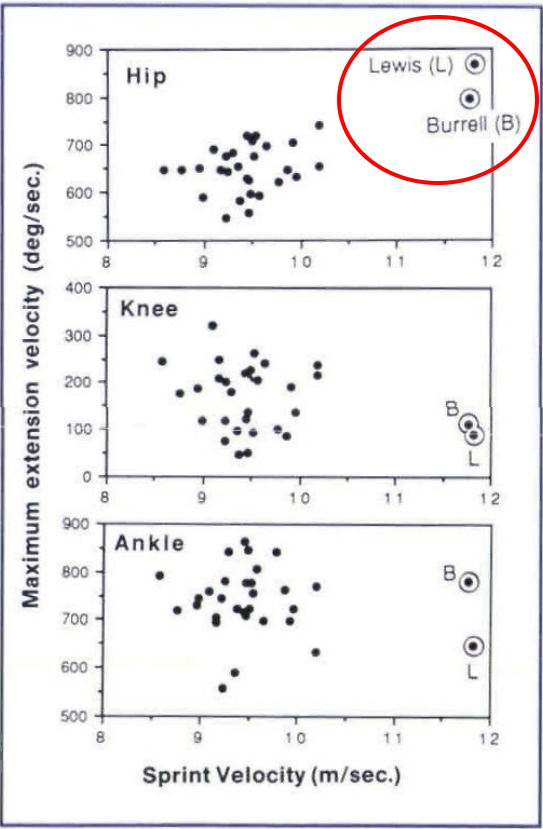

The key force generation movement for sprinting is that of hip extension (gluteals, hamstrings). The faster and more powerfully the athlete can generate a high level of angular velocity through the hip joint on the way to their foot hitting the ground, the more effective they will be at generating high running velocity at top speed. An old, but great study completed at the 1991 World Athletics Championships in Tokyo showed that the first and second place holders (Lewis 9.86, Burrell 9.88) had one main kinematic trait that separated them from all the other sprinters in the race, that was a superior hip extension angular velocity.

To maximise this kinematic capacity in our athletes, we must develop two attributes:

1. The ability to rapidly switch from a hip flexion to hip extension movement, and

2. The ability to forcefully drive the thigh into the ground with as much speed and power as the athlete can generate during their ~4.5strides per second!!

To work on this rapid hip extension, there are several gym exercises that can be used to begin teaching your athletes to perform this dynamic high velocity hip extension movement:

1. Cleans/Snatches – There is a high technical component to these movements and unless the athlete is trained appropriately, these exercises doesn’t activate the hip extensors anywhere near as well as can be achieved with less technical exercises.

2. Dynamic Step ups – Important here is the term Dynamic, a few of my athletes feel the traditional step up is too quad dominant (particularly if the box is too high), so for raw strength we would only step up onto a low box (20cm-30cm) with a high weight (see below for more information on this topic).

But if you want to develop dynamic hip extension strength, then dynamic stepups are a good addition to your routine.

A dynamic step up is one whereby the athlete attempts to drive their foot into the ~15cm box/step as fast and as hard as they possibly can, with a focus on rapid hip extension and hitting the box/step with a flat foot (Dorsiflexed ankle).

This drill is excellent for teaching the athlete to drive vertically down from the hip flexion position. Initially body weight is more than enough to load the athlete, but as the athlete improves you can then start to add weight.

Whilst the above exercises address the rapid hip extension component and Pfaff is very interested in what he calls the “switching mechanism” of the hip – the ability to be able to go from a rapid hip flexion to a rapid hip extension. Now of course sprinting regularly will assist with this drill but I use another exercise that is as much a core exercise as a switch mechanism exercise – and that is the Roman Chair leg switch exercise.

I like this exercise for a couple of reasons:

1. The athlete can focus on a strong posterior/neutral pelvic tilt whilst doing the exercise – thereby reinforcing the correct pelvic positioning when sprinting at speed, and

2. There is great immediate biofeedback, if the athlete performs this exercise well, the force generated will lead to a major shake of the apparatus they are using.

I like to start with two switches (one full stride) and over time as their coordination and conditioning improves, we increase that to 3, 4, 5, etc.

The athlete can really focus on being rock solid through the core whilst trying to move the limbs as quickly as possible through a complete stride (or more).

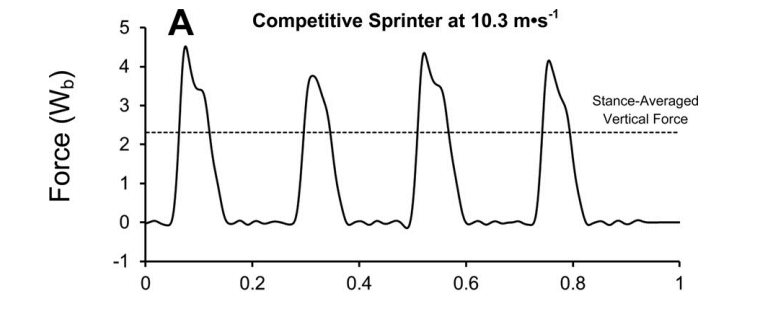

The second factor, Load Tolerance, is related to the capacity of the athlete to not “buckle” when the foot hits the ground at maximum velocity. Recent research has clearly shown that the faster you sprint, the higher the Ground Reaction Forces (force that the athlete applies to the ground) they will experience.

Research by Weyland and Clark (2014) highlighted that elite sprinters will generate up to 5X bodyweight at each ground contact (a 70kg sprinter will have to tolerate 350kg on a single leg!!!). It is not only the legs that need to be able to tolerate this force, it is the entire musculoskeletal system (particularly hips/torso) that needs to be incredibly strong not to collapse at ground contact, but to use it to propel the body to the next step.

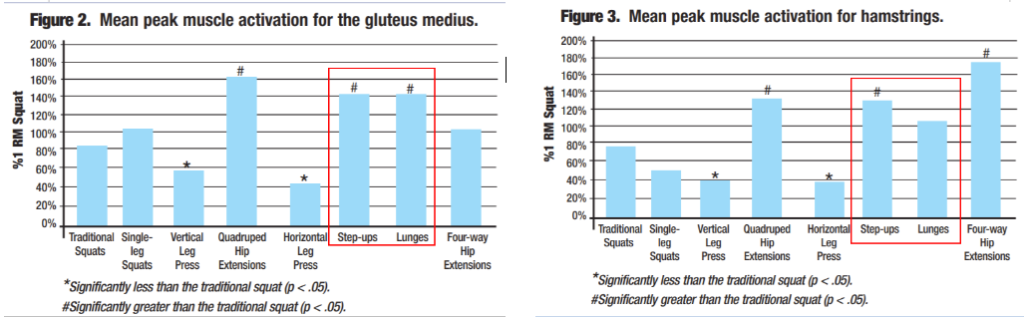

Whilst not a revelation, it is hopefully obvious that single leg gym work should offer the solutions to the above problems.

There are a few reasons:

a. If you lift using a single leg, the weight your torso can tolerate will be closer to the maximum of a single leg, and

b. Single leg training will closer replicate the movement patterns that simulate sprinting, and

c. Single leg exercises lead to greater activation of the hamstrings and in particular the gluteus medius muscle groups (which are vital in the stabilisation of the hip & knee joints at ground contact).

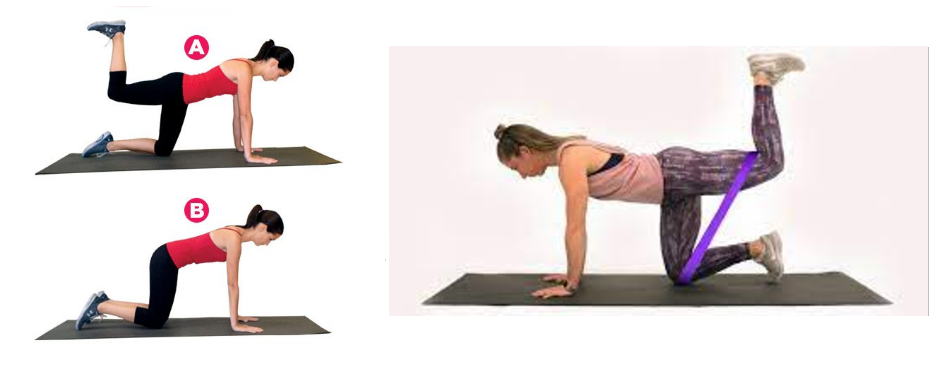

I highlight stepups and lunges as these are the easiest exercises to load your athletes (using traditional bars/dumbbells). The 3rd exercise that is shown to be very good for both gluteus medius and hamstring activation is that of the Quadruped Hip Extension.

It is an exercise that is more difficult to load the athlete, but can be done with bands, but is a great general conditioning and warmup exercise.

A variation on this exercise is the single leg hip thrust and this is where you can start to really load up your athletes and have them focus on strong and powerful single leg hip extension movements.

Important to get some quality coaching with this exercise as it is easy to start using the wrong motor patterns to lift heavy weights off the ground.

Tolerating the GRF at maximum velocity.

This is of particular interest in that there has been some very creative attempts made to improve the athlete’s tolerance to these high vertical loads at ground contact.

Key aspects to note are:

1. The body is largely in an upright position with only small joint angles at knee & hip.

2. The forces are largely vertical.

3. The load isn’t limited to the lower limbs, the pelvis/torso if not strong will also collapse resulting in an ”absorption” phase at ground contact, increasing GCT & decreasing GRF.

What I would like to say at the outset is that deep squats are not the solution to improving this aspect of sprint performance. The benefit to be had from this exercise is in the improvement in total core stability – but there is little specificity in performing a squat over a 45o ROM when you are looking at an almost isometric tolerance at very small joint angles when sprinting at maximum velocity.

Some of the more creative attempts at improving this joint specific strength include:

1. Low Step Ups with Heavy Load

Key here is to keep the box height low (no more than 15-25cm).

What you want to do is to dynamically stepup as quickly as you can with a heavy weight train the entire system to tolerate single leg loads whilst performing a small hip extension movement.

I have a strong memory of the great Arto Bryggare (Finnish 110m Hurdler) performing dynamic stepups with 240kg on his back!!!

He was so dynamic at ground contact that the bar would flex up and down for a couple of seconds after each step!!!

2. Small range squats

This is a two leg version of the dynamic stepups.

You lift a significant weight and then only squat a few degrees (10-15degrees) with a focus on tolerating the vertical load and as explosively as you can extend to a full upright position.

This exercise is much harder on the spine due to the high loads you need to lift.

This type of training is highly neural. As an example, an athlete of mine many years ago was keen to experiment with this small range training to see the effect upon his sprint performance. After our first session of small range squats with 250kg (he was only 68kg in body weight) he was telling me that he went out to dinner with his family after training and fell asleep at the table!!!!

3. Isometric Training

Isometric training has a small effect a few degrees either side of the angle at which you train and so by loading the body isometrically at a range of around 10o from anatomical position, in theory you can develop very high load tolerances throughout the entire anterior and posterior chains specific to sprinting.

As an example, again many years ago, the AIS looked at isometric force production capacities with some of their T&F athletes and one result was a female mid 50kg in weight, able to generate close to 250kg in vertical force against an immovable bar. So being able to have athletes generate huge isometric forces in the right body position may also be a way of getting the body to adapt to the large vertical forces it will experience particularly at maximum running velocity.

The other interesting trial was single leg isometric holds with a focus on holding the ankle in a neutral dorsiflexed position off a step – again with the goal of trying to improve the tolerance of the main joints in the body to the GRF that they will experience during a sprint race.

4. Plyometrics

You can’t have a discussion around developing and tolerating GRF’s without talking about plyometrics.

Plyometrics is the rapid stretching and shortening of muscles around one or more joints with a focus on improving both the tolerance to load and improved stretch shorten cycle (stretch reflex) that can provide some “free” force generation through whatever movement you are undertaking.

I will continue this discussion in Part 3 with a more in depth review of plyometrics (science and application) and how to develop an appropriate plyometric routine that will enhance your athlete’s capacity to both tolerate and increase GRF’s during their sprinting performance.

References:

Weyand PG, Sternlight DB, Bellizzi MJ, Wright S. Faster top running speeds are achieved with greater ground forces not more rapid leg movements. J Appl Physiol 81: 1991–1999, 2000.

Weyand PG, Sandell RF, Prime DN, Bundle MW. The biological limits to running speed are imposed from the ground up. J Appl Physiol 108: 950 –961, 2010.

Kenneth P. Clark and Peter G. Weyand Are running speeds maximized with simple-spring stance mechanics? J Appl Physiol 117: 604–615, 2014.